リンダ・デニス展

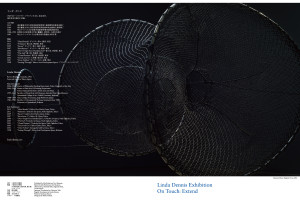

Linda Dennis Exhibition On Touch: Extend

Artist Talk: June 12, from 11am

In Yanagihara Yoshitatsu Memorial Gallery B

2016年4月23日(土)-6月26日(日)

23 April (Sat) – Sun 26 June (Sun) 2016

9:30-17:00(入館は16:30まで)

http://www.bunka.pref.mie.lg.jp/art-museum/54800037876.htm

More exhibition details on NEWS page.

On Touch: Extend, Mie Prefectural Art Museum – Pamphlet (PDF format)

朝日新聞デジタル

http://www.asahi.com/area/event/detail/10210144.html

リンダ・デニス インスタレーション

⇒ 三重県立美術館 学芸室より

リンダ・デニス(1963~ )は、オーストラリア東部の都市・ブリス

ベン出身のアーティストです。

はじめは、大学の薬学部に学び、後に美術に転向しました。彼女の初

来日は1986年。4年間ほど主に九州佐賀の有田で陶芸の勉強をした後、

クイーンズランド州立グリフィス大学芸術学部で研究を重ね、2000年

からは多摩美術大学彫刻科、さらに東京芸術大学の大学院にも学び、

現在は日本と母国とで造形活動を行っています。

デニスは、2014年頃からたびたび三重県南部の紀北町紀伊長島に滞在、

この町で生産される漁網を素材とした立体作品の制作を手掛け、紀北

町はもちろん、東京や高松で発表しています。また、紀北町での現代

美術展創設に大きな役割を果たし、今年開催された【くまの古道美術

展 in 紀伊長島 2016 】でも公開制作を行いました。

その際に制作した作品の一部が今回展示される予定です。

Text by: Professor Pat Hoffie

We live in a world where technology increasingly determines how we relate to the world around us. The terms ‘internet’ and ‘world wide web’ have been borrowed from biological references to ecology. Paradoxically, these terms came into common currency at a point in history when most of the worlds urban-based population spend more time online than they do in the natural environment. And yet, (to weave yet another contradictory strand into this mesh) we have a heightened awareness of ‘nature’ through popular programs that enable us to see aspects of nature that it has never before been possible to visualise. Digital images of ‘nature’ have become so refined, so precise, so high-tech that our own first-hand experience of the world around us may seem diminished and one-dimensional by comparison. Yet while the hyper-visuality of the digital world may suggest an experience that is saturated, abundant and immersive, it is a flattened experience that does not accommodate for other human sensory data that complement and extend the visual.

For over a decade Linda Dennis has focused on touch as a way of apprehending and understanding the world we live in. She is a visual artist who is aware of the way touch has often been overlooked as an important way of extending our sensitivity to each other and to the world around us. Dennis’ experience as an artist is unusual in that her practice is informed by early training in physical rehabilitation: she understands first-hand the way the body responds to certain types of stimulation as well as to sensory deprivation. She has brought this to bear on her deep and long training as a visual artist. This too has followed in an unusual trajectory, as she has continued her studies in both Australia and Japan. She has also experienced first-hand the cultural differences in responses to issues of touch in both countries. This kind of background provides a rich substrata from which to continue her ongoing focus, one that traces pathways that weave divided territories together in new patterns and interdependencies.

Dennis’ commitment to the importance of touch demands that site-specific references are also an important consideration of her work. The location of each of her installations are as much a material consideration of her work as are the media choices she makes. She is aware that the interpretation of work will differ according to where it is experienced. In response to this awareness she underpins her production methodology with research about the location of each site, and this too prepares the way for the selection of materials, themes and outcomes.

For some time now Dennis has been working with fishing nets. Her experience in Mie Prefecture, Japan brought her in touch with the fishing industry that is so important to the local inhabitants there. As part of a series of engagements that included organizing and participating in exhibitions there, doing talk events, negotiating with local inhabitants and artists and planning for future exhibitions, Dennis came into contact with manufacturers of fishing nets, and began a series of work using the nets from the local area as both the material and subject of her work.

As has been mentioned, the ‘net’ has been a key metaphor for understanding the inter-relationships that from the basis of a balanced ecology; in turn, it was borrowed from biology as a term to describe the proposed inter-relationship of the internet – as one that links everyone together in an idealised interactive global equality. It’s possible to read each of these inferences in these works, where the form of the hand recalls the evidence of the community of makers behind the product.

However, in Dennis’ new works these nets appear to also have a more direct reference to their role in harvesting fish. She re-forms these nets into new configurations, some of which make direct reference to the hands that wove them, that held them, that mend them and that in turn reconfigure them into new forms as art, implying in turn the inter-relationship of objects with their makers. The seamlessly smooth imagery of our digital world screens the evidence of handiwork; it covers over the kind of details that invite us to feel how it must have felt to weave the ropes, to cast the nets, to re-structure them into new forms. These are processes that involve the body – they involve all those sensations that enter the body through touch, as well as the processes of thinking; they involve doing as well as being, and they often require community collaboration.

Many of the works Dennis has produced over the years involve processes of interaction as part of the process of viewing the work. This brings us into contact with each other – not only in terms of shared discussion, but also in terms of physical contact. The artist thus weaves the viewer/participant into the work as an integral element – one where apprehension of the work can mean touching each other as well as the materials she has fabricated. Such experiences are often unsettling; they take us beyond the politeness of distanced contemplation. Instead, we are implicated in the outcome of the work’s affect; the artist fabricates a role for us that establishes our place in relation to the work, to each other, and to the place in which it is installed. The site-specific and interactive qualities of Dennis’ work are more complex and multi-layered than ‘gallery art’ pure and simple. They do not only rely on their aesthetic appeal, which is abundantly manifest. Rather, she uses that often minimalist, elegant aesthetic to lure us into a trap where we realise that our role in relation to art is a conjoined one, as are our relationships to the places we inhabit, and to the communities that we form and are formed by.

These values are extended by Dennis into other aspects of her role as an artist – she is also, at various times, a project coordinator, a curator, a writer and an artist-educator. She has been profoundly influential in bringing disparate communities together from different countries, different regions and different dispositions. She does this with skill and grace, and the benefits of these skills are extended to many here in Japan, in Australia and in Britain. But it is her role as an artist that is central to these activities, and her work is testimony to deep convictions and sympathies that are manifestly evident in works of intellectual subtlety and formal elegance.

Professor Pat Hoffie

Director SECAP

(Sustainable Environment through Culture, Asia-Pacific)

UNESCO Orbicom Chair in Communications,

Griffith University, Australia